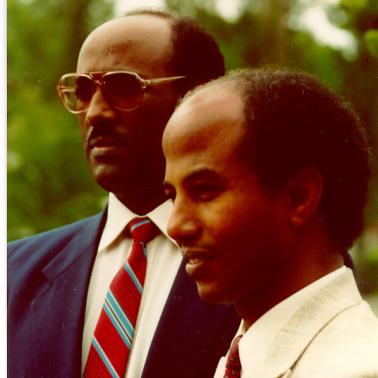

Photo: Fesseha Fre Weri and Osman Ibrahim Shum from Eritrea, one a Christian, one a Muslim, who both came to make their homes in Canada.

I am usually reluctant to tell my story to people because it brings back pain to me. I would like to forget the past. But when I see people who are going through the same pain, like mine or even worse, I pray that Almighty God gives me the courage to face my past pain with the hope of helping others face their own.

When things around you go wrong, very wrong, awfully wrong, you feel resentful, vengeful and confused, lost, bitter and hopeless, in total darkness.

This is what happened to me in the fall of 1970. Before then everything seemed to work well for me. I was a young customs officer with a bright future. My family members were all happy in their village. My father’s beautiful orchard seemed to bloom eternally. The smiles of my villagers were always festive. Muslims and Christians in my village were in total harmony. My father’s orchard was shared by everybody. The guavas that my father grew were delicious. A kilo of guavas then cost less than 1 US cent.

But far beyond my village, in the hills and mountains, the rebel movement for the liberation of Eritrea was building up. One night of early October 1970 a single shot from a gun in the village was heard by the Ethiopian Military in the nearby town of Keren. The next morning was a day of a memorial service for a fellow Muslim villager (or Altfatiha as known in the Koran). There were 800 people gathered from my village and other villages in the area to perform the prayer ritual. The same day the Ethiopian Army descended to the village from all corners and massacred almost the entire people, 730 of them in one hour. Many were burnt alive in their thatched huts. My close relatives, and many dear friends to me were among them. My father and mother were among the few who survived. How they survived is another story, but they witnessed the total destruction of life around them. Their orchard, which later became an army camp, was totally destroyed. Our home was in flames. Our cows and sheep, several dozen at that time, were slaughtered or shot dead.

I wish I [had] witnessed all these atrocities, because the shock would have been gradual and perhaps easier than having it all at once. I came to my village after everybody and everything was in ashes. I melted into myself. The pain was beyond me. I became a dead person.

Forgiving those who caused me pain was a cowardly act, an act of fear and submission to those I called my enemies. The time had come for me to pick up my Kalashnikov gun and join the rest of my compatriots in the mountains. I missed the point that submitting to my anger and feeling for revenge was becoming a worse enemy for me than those responsible for my loss.

A few months before this disaster I had met MRA. I first thought of it as ideology to pacify us Africans to remain stagnant and subservient to the white people. Soon after, I discovered MRA to be a challenge – a challenge to my personal life, a challenge to my bitterness, a challenge to my corrupt behaviour, a strong voice knocking inside my heart. I asked God, “Now that you allow all these things to happen to me, what do you want me to do?” God’s answer came to me: “My clear commandment is ‘Do not kill’. Your sorrow and anger are the result of your transgressing this commandment. I join you in your sorrow.” I prayed for inspiration and courage. I felt the burden of anger crushing me, but I also felt a better calling for my life: was the purpose of my life just to be angry and vengeful? One of my friends asked me, “Do you want to be part of destruction or part of healing? If you want to be part of healing, first heal yourself.”

I thought to put a line between my anger and my person and decided to take my anger and revenge as a sickness that needs cure. That cure was forgiveness. Who should I forgive? A killer? That was hard – impossible. A thought came to me, that forgiveness does not come easily. It came to me through meditation and guidance. My friends in MRA gave me valuable support in helping me root out my bitterness.

Forgiving empowered me to root out my other vices. Through learning how to forgive, I acquired the knowledge of putting my corrupt life in order. As a customs officer you don’t talk about corruption. Your talk about gifts. You receive gifts and the list of the kind of gifts is very long. Some are as small as fleas and others are as big as crocodiles – but they are corruption. I mean Gifts! I faced the reality about corruption in my heart. No ifs and buts. Corruption in my private and public life may vary but, in the end, it has one goal: destruction. It destroys a person, and it destroys a community, a country.

The greatest gift that I received from forgiving those who caused me suffering, is to understand the pain and the loss of others around the world. Now I do know how the Bosnians, for example, felt when they suffered. Seeing others suffer takes me deep into myself and, whenever it happens, wherever it happens, I share it with them.

Last November, I was called to brief 450 Canadian Peacekeepers, who were going to Eritrea and Ethiopia, on the cultures of the region. Together with an Ethiopian gentleman, we organised a group of 20 Eritreans and Ethiopians to help us in this task. One of them happened to be the daughter of the then-Governor of Eritrea who ordered the massacre of my villagers together with many thousands in other villages. Her father was later killed by the Marxist regime of Col Mengistu. It was amazing to see what started with looks of uncertainty at each other ending with hugs and a sense of deep spiritual contact, as we completed the work and parted. Today we speak of the past: a common past of sorrow, and how we can use it for healing the present crisis in our region.

I am happy to say that the peacekeepers have returned to Canada and their mission passed off without a single incident.

I would like to quote part of a poem by George Roemisch that inspires me: Forgiveness is the fragrance of the violet which clings fast to the heel that crushed it.

If perchance we are the ‘heel’ that crushed a violet, this is the time to seek forgiveness. Seek forgiveness from our husbands or wives, our children, our relatives, friends, community members. If we are that crushed violet, we will continue giving out our fragrance so that our world will be a better place.

Fessaha, his wife and two children made their home in Ottawa, Canada, where he retrained as a chef. He died on May 31, 2017 after a courageous battle with cancer.