On May 21st, the third in a series of events called Circles on Indigenous Worldviews took place by Zoom. The presenters were Elder Tina Poucette Fox and her son Trent Fox. What unfolded was a deeply moving and challenging presentation. Elder Tina, a residential school survivor, recounted her experiences of those school years as well as impact on her of the discovery of 215 unmarked graves at a school at Tk’emlups te Secwepemc (Kamloops). Trent presented a series of slides showing the timeline of historical events and the generational impact of the residential school experience.

Elder Tina began by telling us how, at 5 years old, she came to have the Stoney name Îya sa wîyâ. Her grandmother gathered her, her two sisters and a cousin together for a Sweat. In Tina’s words, “She gave my sisters lovely flowery names and to me she said, ‘you are going to be Îya sa wîyâ’ (Great Mountain Woman). I was what you might call ‘sassy’ and said, ‘keep that name for yourself!’ My grandmother tapped me on the knee and said, ‘be quiet’!! Today, I am very proud of that name. It’s a very powerful name. It gives me strength to withstand anything that has happened in my life.”

In 1948 Tina’s parents were informed that Tina had to be registered at the residential school in Morley. Her parents were excited at the possibility for her to be educated and her mother made a beautiful dress for her. “She spent a lot of time tanning deer hide and made me little moccasins. She dressed me up and we went off on a horse-drawn wagon to the school”.

But soon after arriving at the school, Tina and two other new girls became very fearful when their clothes were taken off and thrown in a corner. They were bathed with kerosene, “which stank and stung”. After a shower, they were given different clothes. “I never saw the clothes my mother made again”, said Tina. That winter her mother passed away and she remembered that those clothes were the last things her mother made for her. If she had been given them back, she would still have them today.

During her time at the school, Tina was physically, sexually, mentally and spiritually abused. In her words, “After spending 11 years being told you are a ‘dirty little Indian, good for nothing’, you come out of school with no self-esteem whatsoever, feeling you are never good enough, always feeling like there’s something wrong with you”.

In the nineties Tina’s community held workshops on inner healing, which helped her and many women to deal with all the anger, resentment and hurt that they felt. She said, “I was able to ‘ease’ my anger and hatred and life became peaceful for me.” The saying ‘the abused become the abuser’, is true for her. However, today she is grateful her children are doing okay and she has a good relationship with them.

When the gravesites of the children in Kamloops were found last year and as the Elders were telling their stories, wounds were reopened for Tina. Students older than she remembered that kids from her community had disappeared and never came home. She fears that when they begin the search, more wounds will be reopened. “But this is what we have to live with. We get on with our lives, but then something happens, and it triggers (the wound) right away.”

“We cannot live in hatred”, she went on to say. “We need to find a way to forgive – forgive, but never forget.” She has gone through a process of forgiving those who abused her. “I forgave them and that freed me from the hatred I had in my heart. In our community, we have a lot of addictions which we use to numb out, so that we can live our lives. We need more healing workshops, because they deal with the core issue of what we’re trying to numb out.”

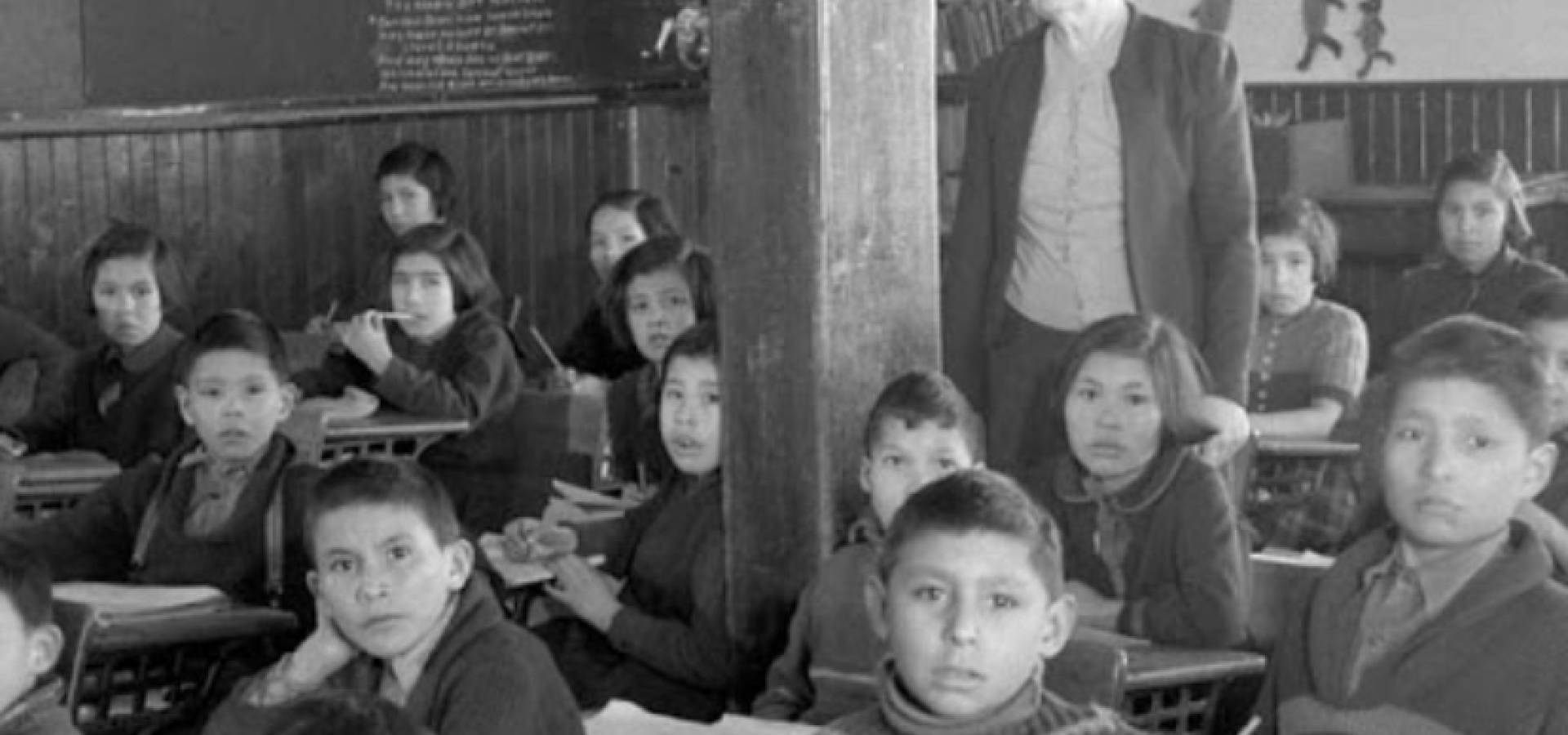

The fallout from residential schools passes from generation to generation, as Trent knows from experience, and continues to affect today’s younger generation. Through a series of slides, Trent showed participants a timeline of historical events. His presentation was appropriately named ‘Every Child Matters’ and he took his listeners through the beginnings of residential schools in 1831 and Prime Minister Sir John A. McDonald’s declaration that Indian children were to be withdrawn from parental influence, to “kill the Indian in the child”. The intent was not only to educate, but to destroy the entire Indigenous cultures and languages. Unbelievably, in 1907 Dr. P Bryce reported that the health conditions in these schools was a national crime! Nothing was done about this report. In 1969 the Federal Government took over the running of the schools from the various churches.

As mentioned by Tina, their community is dealing with alcohol and drug addiction. For her family alcohol had been part of their lives, but now for the first time in her life, Trent says, “my mother has sober children and the family is living meaningful lives.”

Trent asked the question: “How can we have reconciliation when students are not taught the truth?” In school he was taught about the Treaties, but not about what happened in the residential schools. He believes reconciliation will take time, but that it must start at home, with Indigenous communities, families, friends, and nations.

The truth needs to be told! The history of Indigenous peoples and their cultures needs to be taught fully in schools. How can we, non-Indigenous people understand Indigenous issues if we are not taught about them? There are plenty of opportunities for non-Indigenous people to learn more. It’s up to all of us to be part of the healing every day, as we face the truth. I challenge myself to stand in solidarity with the truth, respecting those who think differently to me, there is always common ground on which we can agree and on which we can move forward.

The words of Trent written after the event challenge me more as I reflect on his comments: “As Indigenous people, we live in a timely world as opposed to a timed one, (a world not governed by the clock, but instead by when the time is right). My mother has been able to overcome her anger and I am personally grateful that there are non-Indigenous people who are willing to learn and appreciate the truth. Films like ‘We were Children’ and ‘Indian Horse’ tell important stories. I view non-Indigenous people from all walks of life as ambassadors who can advocate learning the facts before rendering judgement. If we can influence one person, he or she can influence others. Îsniyes, pinamaye.”